Valentine’s Day is upon us yet again. Chances are, you and your sweetheart will find yourselves together in a restaurant on February 14th. Roses may be gifted, chocolate confections may be consumed, and to drink – why, champagne of course. Is any other spirituous potable more synonymous with love than a bit of bubbly? The clinking of flutes or coupe glasses is an unmistakable counterpoint in the soundtrack of virtually every wedding and anniversary celebration.

You may be surprised to learn that champagne has not always been the crystal-clear, diminutively effervescent libation we know today. It was once an overly sweet potion with large bubbles. Often, it was clouded with fermentation yeast that could alter the wine’s taste, and not for the better. But that all changed in the early 1800s, thanks to an enterprising young woman, who forever changed the French wine industry.

A Widow Makes Her Mark

Barbe-Nicole Ponsardin was born in 1777 to a wealthy family. Her father, Nicolas, was to become a well-connected Baron who once hosted Napoleon and Josephine at his hotel. At the age of twenty-one, Mademoiselle Ponsardin married François-Marie Clicquot and became Madame Clicquot. Her marriage was not to be a long one. François passed away a mere six years after their nuptials, leaving Mme. Clicquot a widowed mother in charge of the Clicquot business holdings, which included a stake in a vineyard as well as a wine-making operation. The Veuve (French for “widow”) Clicquot focused on the wine trade. She was not an overnight success. Under François’ tutelage, the wine business had flourished. However, under Mme. Clicquot’s early watch, sales plummeted from a previous high of 60,000 bottles per year to only about 10,000 bottles per year.

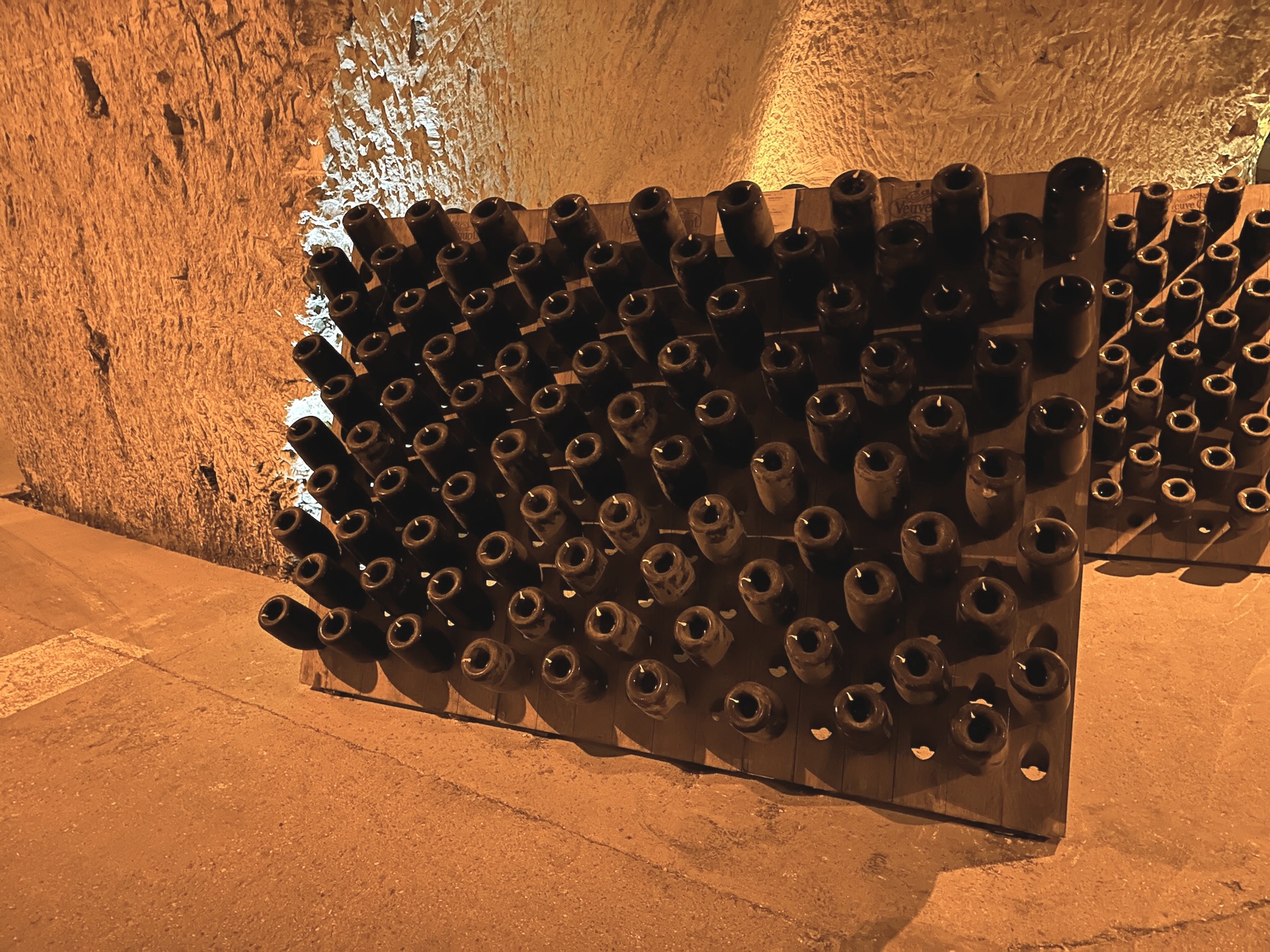

Undaunted, she focused on methods of production. With the assistance of her loyal cellar-man, Mme. Clicquot perfected the remuage or “riddling” process in 1810. During the second bottle fermentation, which gives champagne its fizz, Mme. Clicquot placed the bottles at an upside-down angle in racks and rotated them at regular intervals for several weeks. The yeast collected in the neck of a bottle and was removed. The bottle was then topped off with a bit more wine and re-corked. The final product was the crisp beverage to which we are accustomed. Although now automated, essentially the same method is used still today.

Thanks to Mme. Clicquot’s innovation, she had a superior product. But against the backdrop of European civil and political unrest caused by the ongoing Napoleonic Wars, selling Veuve Clicquot brand champagne was a substantial challenge.

A Distinctive Look for a Distinctive Product

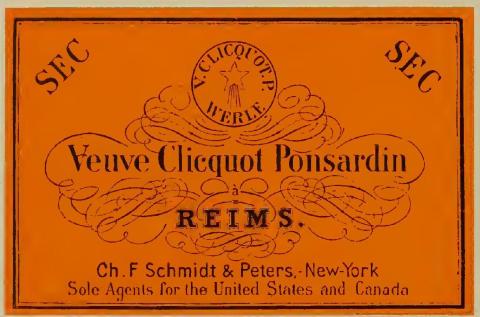

As Mme. Clicquot struggled to establish her market, she also had to confront the production and sale of counterfeit concoctions. It was the practice of the day to sell wine in plain bottles, so any huckster could try their hand at reselling cheap swill as something else for a tidy profit.

Mme. Clicquot made a habit of suing those who fraudulently represented their lesser wares as her fine wine. She also began marking her corks with an anchor to try and thwart the ne’er-do-wells. In 1811, the Great Comet was visible in the night sky. Mme. Clicquot, showing an early mastery of the timely tagline, referred to her champagne as le vin de la comète and added a star to the cork, along with the initials VCP, short for Veuve Clicquot Ponsardin. Many of these branding elements continue in use to this day.

In the Royal Courts of Europe, Lifestyle and Brand Come Together

But Veuve Clicquot became more than just a commercial success; it soon became part of the fabric of 19th Century political and cultural life. Amid a trade embargo in 1812 imposed by the Russian Czar, Mme. Clicquot secreted thousands of bottles of champagne inside coffee barrels so they could be smuggled into Russia on a cargo ship. Russia’s nobility represented the height of opulence, and they would prove to be a lucrative standard bearer for the brand. By 1814, Napoleon was in exile, and trade routes again opened. Russia greeted with open arms a ship carrying only Veuve Clicquot champagne.

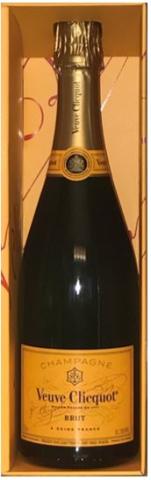

In 1814, the winners of the Napoleonic war, along with the new French Bourbon regime, convened at the Congress of Vienna, the most important political event of the era and a also great party that stretched into the following year. Mme. Clicquot seized the opportunity. Thanks to her stellar promotion, Veuve Clicquot champagne flowed freely at the grand gatherings of the nobility and the political elite. By the dawn of La Belle Époque several decades later, champagne ran like a river through the streets of Paris. Without it, your celebration was not a party. Champagne was literally and figuratively the drink that made society “high.” By mid-century, the signature orange label, long since a registered trademark, was added to the bottle, putting the finishing touch on Mme. Clicquot’s namesake brand.

So this year, as you sip champagne with your special someone, give a little wink to Mme. Clicquot. After all, she made these moments all the more special. And if you are ever at a loss for what to say when you raise your glass, you can always recite these words, “Je propose un toast en l’honneur de la Veuve Clicquot.”